Sea level rise after the last ice age: more knowledge

Thanks to new geological data, we now know more about how fast and how much the global sea level rose after the last ice age, some 11,700 years ago. This information is of great importance for our current understanding of the impact of global warming on ice caps and thus on sea level rise. Researchers from Deltares, Utrecht University, TNO Netherlands Geological Service, Delft University of Technology, the Netherlands Institute for Sea Research (NIOZ), University of Leeds, University of Sheffield, University of Amsterdam, LIAG and BGR published their findings in the journal Nature.

Download the findings in Nature

Better understanding of sea level rise

The new knowledge into the rate of sea level rise during the early Holocene offers an important point of reference for scientists and policymakers, especially as we are now faced with a similar situation with rapidly melting ice sheets due to global warming. The research provides valuable new insights for the future.

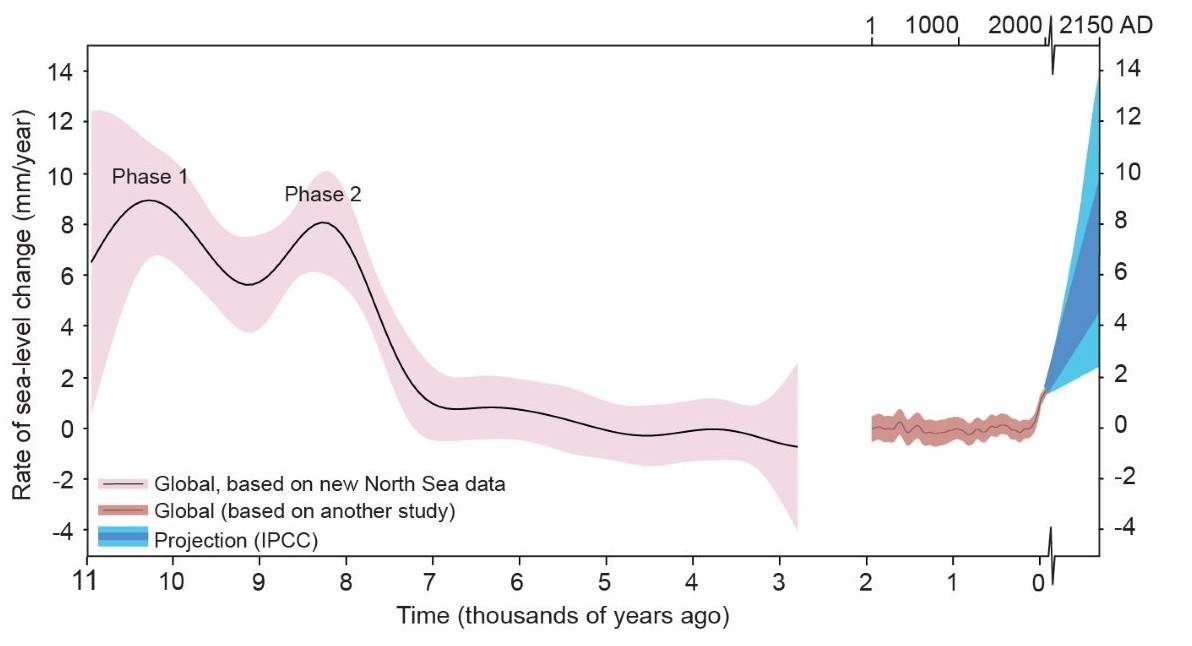

As a result of the current rise in greenhouse gas concentrations, climate models by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) expect sea levels to rise by several metres by 2300. Some scenarios indicate a rise of more than one metre per century. An important difference with the early Holocene is that the consequences of sea level rise are far greater today and in the future. This is due to a growth in population and the current presence of infrastructure, cities and economic activity.

With this groundbreaking research, we have taken an important step towards a better understanding of sea level rise after the last ice age.

Marc Hijma, geologist at Deltares and the lead author of the study

Unique dataset in the North Sea region

Global sea level rose quickly following the last ice age. This was as a result of global warming and the melting of enormous ice caps that covered North America and Europe. Until now, the rate and extent of sea level rise during the early Holocene were not known due to a lack of sound geological data from this period. Using a unique dataset for the North Sea region, the researchers have now been able to make highly accurate calculations for the first time. They analysed a range of boreholes from the area in the North Sea that was once Doggerland, a land bridge between Great Britain and mainland Europe. This area flooded as sea level rose.

By analysing the submerged peat layers from this area, dating them and applying modelling techniques, researchers showed that, during two phases in the early Holocene, rates of global sea level rise briefly peaked at more than a metre per century. By comparison, the current rate of sea level rise in the Netherlands is about 3 mm annually, the equivalent of 30 centimetres per century, and is expected to increase.

Furthermore, until now there has been considerable uncertainty about the total rise between 11,000 and 3,000 years ago. Estimates varied between 32 and 55 metres. The new study has eliminated that uncertainty and it shows that the total rise was around 38 metres.

Groundbreaking research

Marc Hijma, a geologist at Deltares and the lead author of the study: “With this groundbreaking research, we have taken an important step towards a better understanding of sea level rise after the last ice age. By drawing on detailed data for the North Sea region, we can now better unravel the complex interaction between ice sheets, climate, and sea level. This provides insights for both scientists and policymakers, so that we can better prepare for the impacts of current climate change, for example by focusing on climate adaptation.”

The paper, ‘Global sea-level rise in the early Holocene revealed from North Sea peats’, was published in leading scientific journal Nature today.

You have not yet indicated whether you want to accept or reject cookies. This means that this element cannot be displayed.

Or go directly to: