Foundation damage in the Netherlands mapped out for national approach to foundation problems

More and more Dutch people are being faced with damage to foundations. Foundations are sensitive to rising and falling land levels, as well as low groundwater levels and therefore dry conditions. Climate change is amplifying the problem. A new analysis by Deltares in collaboration with TNO that was commissioned by the Council for the Environment and Infrastructure (Rli) indicates that, in the short term, there are about 425,000 buildings with an expected technical lifespan of less than fifteen years. Just under a quarter of them are founded on wooden piles; the remaining buildings have shallow foundations.

The analysis was part of the Rli advisory report ‘Well founded: recommendations for arriving at a national approach to foundation problems’ (in Dutch only) , which was published recently. The Rli asked Deltares and TNO for an overview of the current technical knowledge about the nature and extent of foundation problems. Deltares contributed its knowledge about the subsurface and foundations, and TNO its knowledge about the superstructure, the building on the foundations. The current knowledge was used as the basis for Chapters 3 to 6 of Part II of the Rli advisory report.

Technical, financial and societal problem for much of the Netherlands

Damage to the foundations of buildings is a growing and complex problem, and it is seen in large parts of the Netherlands. It is a consequence of living in a low-lying country with soft soil. It is not only a technical and financial problem but also a significant societal problem, as seen by homeowners of older properties on soft soil. Despite the fact that foundation problems have been subject to research and action for decades in older cities in particular, there is still little awareness of the issue in many other regions. The Rli report states that a national approach is needed to address foundation problems effectively.

Causes and extent of foundation damage

Foundation damage is often the result of a succession of local changes (in groundwater levels, for example), processes in the subsurface and foundation quality. Examples include rising or falling land levels resulting from consolidation, creep, the oxidation of peat and the shrinking or swelling of clay. Depending on the type of foundations – shallow or on wooden or concrete piles – this can have effects such as the deterioration of wooden foundations, negative skin friction, differential deformation or a loss of load capacity. That results in visible damage to buildings such as warping, cracking or damp.

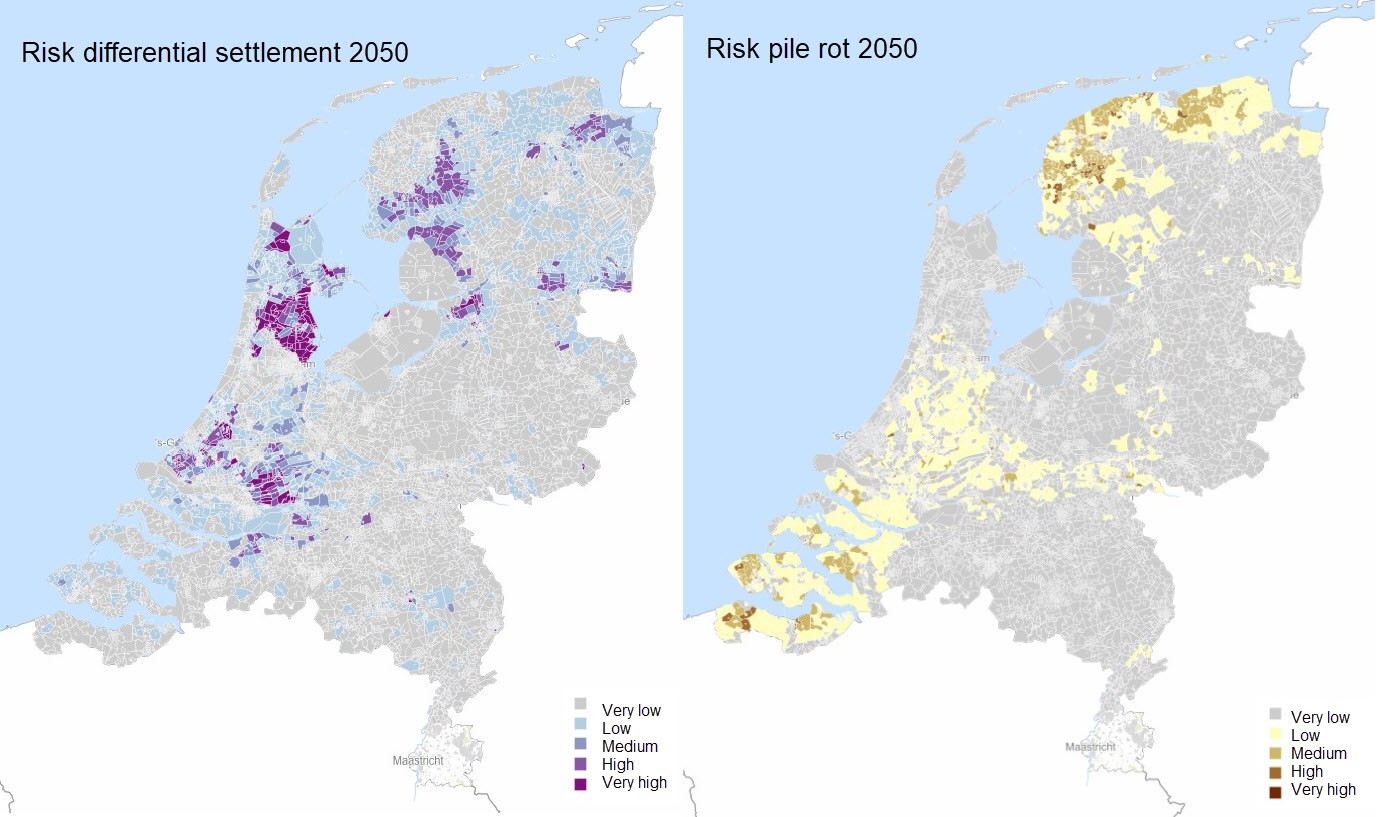

On the basis of the foundation risk model developed by Deltares, it has emerged that a large proportion of buildings in the Netherlands are at some degree of risk. What is new is that, drawing on available data, we have made more specific estimates of how many buildings nationwide are vulnerable: some 425,000 buildings have an expected technical lifespan of fifteen years or less if no measures are taken. Just under a quarter of them are founded on wooden piles; the remaining buildings have shallow foundations. Buildings with concrete foundations are usually not vulnerable. Over the next 25 years, this number could increase considerably, mainly because of an increase in the number of buildings with shallow foundations rendered vulnerable by climate change.

We have a good understanding of relevant local changes such as groundwater levels, and of processes in the subsurface and foundations. Even so, we cannot state exactly at present which buildings are vulnerable or not. This requires more data about the types of foundations used for individual buildings in the Netherlands.

Mandy Korff, Deltares foundation engineering expert

Moreover, vulnerability depends on the properties of the building, the subsurface and changes in areas such as climate or policy. An example is the raising of water levels, which can have both positive and negative effects on foundation problems.

Assessing the condition of foundations and technical measures

Deltares and TNO are advocating a coarse-to-fine approach to assessing the condition of foundations. A first step will be to study source documentation, looking at construction drawings or archive documents for example. A second step may be a survey of the condition of the building above the surface. The final and most invasive step could then be a fully-fledged investigation of the foundations underground.

If the condition of the foundations proves to be unsatisfactory, technical measures will be required. There are technical measures for existing buildings, newly-built buildings and public spaces to reduce or prevent the effects of foundation problems. Some examples include repairing damage, groundwater level management and the installation of completely new foundations (with piles or otherwise).

More specific information and knowledge needed

At present, it is not yet clear at the national level how many foundations of existing buildings are susceptible to problems, how many have already been repaired in the past, what the current quality of the foundations is, and how the problems could develop. As a result, we cannot now say exactly which buildings are vulnerable or not. Moreover, vulnerability depends on the properties of the building, the subsurface and changes in areas such as climate or policy. A better estimate is needed so that the government and homeowners can take more effective action. This mainly involves collecting information about the foundation types of each building, regulation and better modelling for groundwater, the development of knowledge about the shrink-swell behaviour of clay, and monitoring and mitigation of land subsidence. In the years ahead, Deltares will continue with its efforts to develop an ever better understanding of the nature and extent of foundation problems and the effectiveness of technical measures.